Does the Chit-Chat Ever End?

How to control a chatty classroom

There are days when it feels like the talking never stops. Hands shoot up before questions are finished. Ideas spill out before directions are complete. And side conversations seem to multiply no matter how many times you say, “Eyes up here, let’s get quiet, turn around.”

The truth is, most blurting and sidebar conversations are not signs of disrespect. They are signs of excitement, energy, attention, and sometimes anxiety. Students’ brains are working faster than their self-control, and in some cases, the brain’s impulse control lags far behind. The goal is not to silence them but to help them recognize their impulsive reactions and teach them strategies to regulate.

Understanding what drives this chatter begins with the brain and with the routines you have in place.

The Science Behind Blurting Out

Although blurting out or talking to a neighbor may seem like a willful disruption, it often happens before the brain has time to engage its pause function. The reaction feels automatic, not intentional. This common classroom behavior is rooted in the still-developing neural networks that govern impulse inhibition and self-control.

Here is a closer look at the brain systems involved in controlling the urge to blurt:

The Prefrontal Cortex (PFC): This is the brain’s “CEO.” It houses the executive functions, including the inhibition control needed to stop a verbal impulse. Since the PFC is the last part of the brain to fully mature (often well into a person’s twenties), a student’s lack of “pause” is a matter of neurological development, not necessarily defiance.

The Amygdala and Emotional Impulses: The amygdala processes emotions. When a student is excited, frustrated, or anxious, the amygdala can fire up strong emotions that override the rational PFC, causing a thought to be “launched” as a blurt before the student can consciously filter it.

The Brain’s Attention Networks: Blurting is often a failure of selective attention. When a student focuses entirely on the answer they have formulated, their attention network may ignore the social context (the rule about raising a hand) or the auditory input (the teacher still speaking), leading to an immediate verbal release.

Stop Blurting Out

Helping students manage impulsive speech begins with awareness. Start by drawing attention to what blurting feels like in the body, a rush of energy, a thought that feels too big to hold in, or words that slip out before they are ready. When students can name that sensation, they can begin to interrupt it.

Introduce a visual cue for self-control. Teach students that when they recognize blurting in themselves or others, they can cup a hand over their mouth and take a slow deep breath. Practice it together, make it a fun challenge, and emphasize that it is not a punishment. It trains the brain to notice the behavior and reset. The goal is regulation, not shame. With time, students learn to notice the impulse, use the cue, and wait their turn to speak.

The first few weeks take patience, but consistency turns this practice into habit. Over time, students begin reminding one another, creating a shared rhythm of speaking and listening that steadies the classroom.

Blurting is not a sign of disrespect or disinterest. It signals that students need more guided practice to strengthen their self-regulation skills. Each time a student pauses, breathes, and waits to speak, the brain rehearses self-control, building the pathways for stronger attention, empathy, and classroom harmony.

Fostering Success Through Prevention Strategy

Science confirms that blurting is a failure of the brain’s impulse inhibition. Your goal, therefore, should not be to punish the behavior but to create a classroom environment so predictable and structured that it reduces the impulse load on students’ brains. The strategy, Fostering Success Through Prevention, works by establishing an essential, temporary “external pause function” until students’ internal self-control fully develops.

This method is rooted in brain science: using signals for transitions, visual schedules, and positive routines all reduce the cognitive friction that leads to impulsive outbursts. Instead of relying on a student to suddenly activate their underdeveloped Prefrontal Cortex, you are building systems that preempt the emotional spike of the Amygdala. This creates a rhythm where the brain is less likely to lose its balance.

Teaching proactive procedures while providing clear structure directly supports the development of the executive functions needed for long-term self-management. Although you may have seen, or even used many of these, they are worth sharing again, providing insights as to why they have stuck around so long.

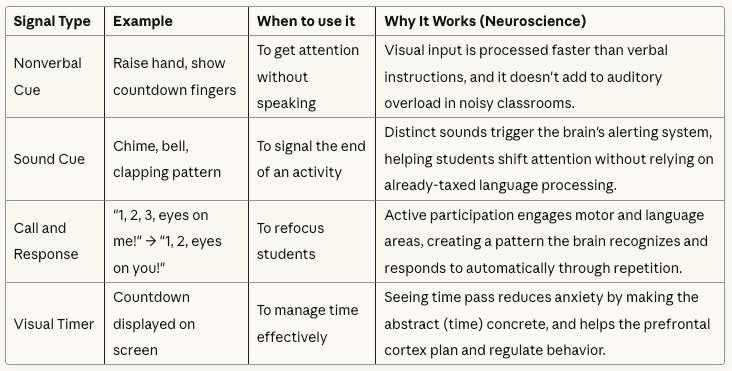

Putting Signals into Practice

These attention signals work because they create neurological shortcuts. When used consistently, students’ brains begin to recognize and respond to these cues automatically, freeing up mental resources for learning rather than behavioral regulation.

Implementation Tips:

Teach explicitly first. Model each signal, practice it, and explain why you’re using it. This builds the neural pathway.

Use consistently. The brain learns through repetition. Pick 2-3 signals and use them daily until they become automatic.

Combine strategically. Layer signals for maximum effect—use a nonverbal cue to get attention, then point to the visual timer to show how much time remains.

Beyond Signals: Building the Complete Prevention System

Attention signals are just one piece of the prevention puzzle. To fully support students’ developing executive function, pair these signals with visual schedules, teach simple self-regulation tools like breathing techniques, and reinforce positive behaviors with specific praise. Prevention isn’t about more rules—it’s about removing obstacles that make self-control unnecessarily difficult.

Another way to channel student energy into sustained focus? Turn it into a game.

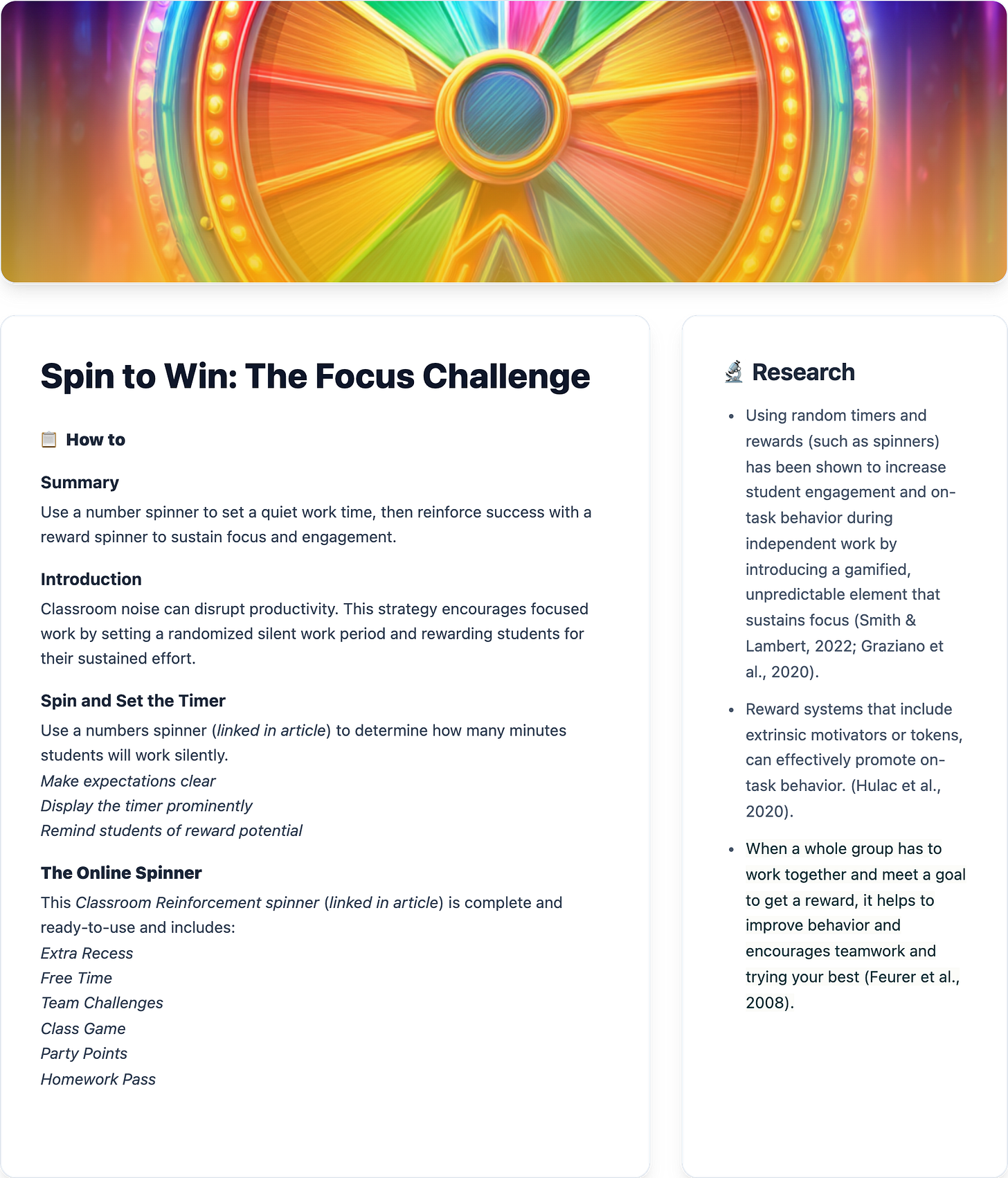

Spin to Win: The Focus Challenge

From a brain standpoint, this strategy approaches blurting and chatter from the opposite direction but reaches the same outcome. Rather than calming the impulse before it starts, it channels students’ focus into a structured, reward-based cycle that sustains attention and self-control.

Classroom Reinforcement Spinner

The Path Forward: Small Shifts, Lasting Change

Blurting isn’t a behavior problem to eliminate. It’s a developmental stage to guide. Every time you use a consistent signal, post a visual schedule, or teach a student to pause and breathe, you’re not just managing a classroom. You’re building the neural pathways that will serve them for life.

The strategies in this article work because they align with how young brains actually develop. They remove unnecessary friction, create predictable rhythms, and give students the external structure they need while their internal controls are still forming. This isn’t about perfection. It’s about progress.

Start small. Choose one signal. Practice one breathing technique. Spin the timer once. Watch what happens when you stop fighting against impulsivity and start working with it instead.

The talking won’t disappear overnight, but the chaos will begin to shift into something more manageable: a classroom where students feel safe enough to learn self-control, structured enough to practice it, and supported enough to succeed.